Sylvia, His Cherie Amour

A MATTER OF CREDIT, EXPLORED IN A NEW BOOK

Let’s revisit that photo. After all, isn’t it one of Motown’s most memorable, capturing a magic moment in Studio A?

The star, of course, is Stevie Wonder – although the musicians shown with him stand tall in Hitsville history, too: James Jamerson, Earl Van Dyke and Robert White. And then there is the songwriter…

Together in the Snakepit, in 1967

Sylvia Moy is striking in her pose and elegance, her beauty evident, with her right hand, placed on the grand piano at which Wonder is sitting, reinforcing the music connection. The shot is also unusual in that most women photographed in the Snakepit are Motown artists, immediately recognisable. Moy is familiar to those with a thorough knowledge of the company’s history, but not beyond.

And that’s the point of singling out Sylvia here and now, as the subject of a new book, It’s No Wonder: The Life and Times of Motown’s Legendary Songwriter, Sylvia Moy. The author is Margena A. Christian, an academic and former journalist with Ebony and Jet magazines. The latter skills are evident in the biography, which dives deep into its subject and, in particular, her significant role in Stevie Wonder’s creative evolution.

Christian’s central thesis is that Moy, as a woman, was denied proper credit for that role – certainly in contrast to the males of Motown – and never properly acknowledged as one of the producers of the hits which rebirthed Wonder at a difficult moment in his career.

Even those who knew, years ago, that Moy was co-writer of “Uptight (Everything’s Alright),” “I Was Made To Love Her” and “My Cherie Amour” were not, according to Christian, aware that she helped to produce those Wonder milestones – nor did she earn what she deserved in that capacity.

The author makes her case convincingly, but what is also notable about It’s No Wonder is the extent to which she interviewed Moy’s contemporaries at Motown, and the candour she encouraged. Thus, among those quoted in the book are Ivy Jo Hunter, Barrett Strong, Janie Bradford, Eddie Holland, Pat Cosby, Paul Riser, Cornelius Grant, Martha Reeves and the Andantes’ Louvain Demps, as well as Smokey Robinson and – perhaps most importantly of all in this context – Mickey Stevenson, once the company’s all-powerful A&R chief.

‘THEY GAVE HER A HARD TIME’

Aside from the topic at the book’s centre, such outreach is important because the number of individuals from Motown’s glory days who are still with us is shrinking, inevitably. First-hand recollections count for more, especially as Moy herself died in 2017 – and since speaking to Christian, so have Strong and Hunter. Fortunately, she was also able to interview several of Moy’s siblings and other family members, who provided invaluable insights into her childhood and upbringing. “My grandfather used to tell my grandmother, ‘I was made to love you,’” recalls Jackie Boyd, Moy’s nephew. “That’s where I remember hearing that all the time.”

“She taught herself at church and at school,” says brother Ronnie Moy, “because she was always in the choirs and in the choir rooms. Anywhere she could find and use a piano or any other instrument, she spent time on it.”

Louvain Demps is in no doubt as to Moy’s importance. “All of these years later, it should be known Sylvia produced many of the great songs that she wrote, but they wouldn’t give her label credit for producing. She was the first female producer we had, and she was warm and had it together. They gave her a hard time, but you could not deny her place because she was good.”

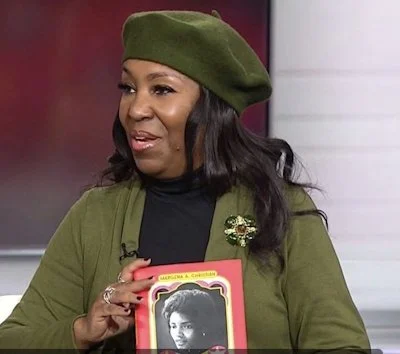

Author Margena A. Christian, with her work

(Technically, it could be argued that Raynoma Liles Gordy was Motown’s first female producer, notwithstanding the fact that she was deeply involved in the company’s start-up through her partnership with Berry Gordy. Among her label credits as a producer were tracks by the Supremes, Jimmy Ruffin and Popcorn & the Mohawks.)

The most influential chauvinist in Moy’s story? Mickey Stevenson, who confesses as such. “[The women at the company] used to call me some terrible names because I would not allow women to produce,” he tells Christian. “For me, you had to come with the attitude of really learning how to produce the product.”

Stevenson adds, “If you’re not strong enough to control the musicians in the studio to get what you want, then you’re not a producer. That took another learning process. Since that was my point of view and my job, I went at it with a passion.”

About songwriting with Moy, he says, “We would sit at the piano for hours. Sometimes we wouldn’t be working on a song but talking. I wanted to get inside of her head because I could see that she could be better…I was inspired to do that with her. We wrote songs together. You know I had to be inspired to write songs with her.” (Even so, Stevenson found no reason to credit or compliment Moy in his 2015 autobiography, The A&R Man. Her name does not appear there.)

Another central Motown figure cited in It’s No Wonder is Moy’s fellow songwriter, Hank Cosby. “She often shared with Hank her anger and complaints about others who did not co-write her songs, but demanded interest in them,” says her sister, Celeste Moy. The late Cosby’s wife, Patricia, recalls an occasion when “one of the guys pulled him aside and said, ‘Don’t be trying to feed her all that information. She doesn’t need to know it. She won’t be here that long, no way.’ Hank responded, ‘She’ll be here as long as I’m here.’”

‘GIVE HIM TO ME’

Putting the matter of credit to one side for a moment, the most insightful part of It’s No Wonder describes Moy’s role in Stevie’s second life at Motown, after his declining post-“Fingertips” record sales put him in contractual peril. Christian quotes Janie Bradford: “I did hear...that [Mr. Gordy] was thinking about letting him go at some point when he ran cold. We were not getting hits.”

The book also retrieves recollections from Moy of the Motown meeting at which Mickey Stevenson sought in-house support for working with the youngster. “I’m going to ask for volunteers and that’s [for] Stevie Wonder,” she recalls him saying. “He made that announcement and all the guys just turned it down. So he says, ‘Well, I think we’re going to let him go.’” At which point, Moy sought to be assigned. “I was begging. ‘Give him to me. Please let me have him.’”

‘Anywhere she could find a piano…’

Handed the task, Moy initially focused on his voice. “Sylvia learned opera,” says Jackie Boyd. “She started teaching him how to breathe properly and sing properly.” Paul Riser elaborates: “As he was struggling with lyrics maybe and melody, she would hear it right away. He’d give her an idea, she’d take it and expand it. They worked together well.” Riser also contends there was a spiritual connection. “And they loved each other. Oh, Stevie loved Sylvia. He did. He trusted her.”

The proof was in the hits which followed, including “Uptight (Everything’s Alright),” “I Was Made To Love Her,” “Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Doo-Da-Day” and “My Cherie Amour”– all Top 10 pop successes, all authored by Moy, Cosby and Wonder. About Cosby’s role, Moy noted in a 1986 Q&A with Richard Pack for Soul Survivor magazine: “His input was more arranging and putting together the track. The vocal melody and the lyrics and chord progression was usually Stevie and me.” In the interview, she also raised the issue of production credit, “although I never got label credits for it, although I did get producing royalties.”

Margena Christian is right to re-excavate the disadvantages that a woman as talented as Sylvia Moy felt during the 1960s and since – not that the issue has gone away today – even though the songwriter periodically raised it herself. “I have to admit as a woman I suffered as a writer,” she told the Detroit Free Press in 1973. “A woman has to be twice as good to prove herself,” she asserted to performing rights organisation BMI in 1977. “There were opportunities for women at Motown fortunately, but there were still certain areas [where] it was harder for women than the men,” she told me in 1991. “A woman producing? So I really had to prove myself and earn that respect as a producer.”

This evocative and very human tale deserves its place on every Motown fan’s bookshelf. Now if only someone can reach Billie Jean Brown to write that biography as thoroughly as this one…

Music notes: after Sylvia Moy left Motown in 1972, she signed with 20th Century Records. One of her releases there as a singer was “And This Is Love,” a song she wrote with Shorty Long; it was also cut at Motown by Gladys Knight & the Pips. Later, Moy formed Michigan Satellite Records, recording Ortheia Barnes (J.J. Barnes’ sister) and Marcus Belgrave. Later still, she hooked up with Britain’s Ian Levine, working to record many ex-Motown artists for his Nightmare label. This WGB playlist features some of Moy’s best-known songs, including her own recording of “My Cherie Amour.”

Sibling notes: in a book as well-researched as It’s No Wonder, small revelations appear. One is that a songwriter by the name of Victoria (Vikki/Vicki) Basemore is Kim Weston’s sister. She is credited as a co-writer on several Jobete songs, including “With A Child’s Heart,” a Top 10 R&B hit for Stevie, and “Lois,” which she penned with him and Clarence Paul. Also, “I Can’t Take It,” an early Martha & the Vandellas track, co-authored with Berry Gordy. Basemore continued her professional association with Weston’s husband, Mickey Stevenson, after he left Motown, writing with him, Leon Ware and Clarence Paul, among others.