Got To Give It Up

THE STARS WHO QUIT WEST GRAND

Ronald, Rudy and O’Kelly must have been excited during those first weeks at Motown in late 1965. The Isley Brothers hadn’t scored a significant hit since 1962, and now here they were, newly inked to the hottest label in the record industry and working with its finest songwriters, producers and musicians.

As the year came to a close, the trio were busy recording tracks such as “Seek And You Shall Find,” “There’s No Love Left,” “What Becomes Of The Brokenhearted” and “This Old Heart Of Mine (Is Weak For You)” – the last of which was to become a Top 20 smash for them by the spring.

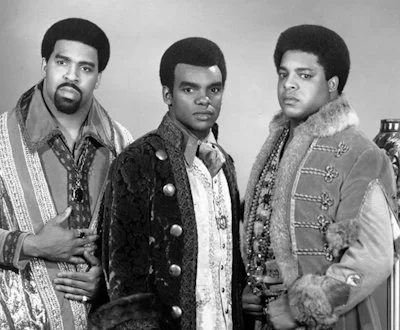

The post-Motown Isleys (as if you couldn’t tell)

Three years later? From Hitsville U.S.A., the Isleys were gone. It was by their own choice, and (as previously documented) was swiftly followed by an acrimonious legal dispute with the company, which claimed that “It’s Your Thing” – the group’s first post-Motown hit – was created while they were still under contract to Berry Gordy’s business.

Welcome to this West Grand Blog look at the acts who quit Motown for other pastures, which frequently led to lawsuits, court cases and all-round unpleasantness. In some cases, the talent’s exit yielded greater success elsewhere; in others, not so much.

The Isley Brothers certainly were beneficiaries, as the statistics below indicate. They sought a release from their Motown recording and publishing contracts in December 1968, and it was granted. Setting up their own label, T-Neck, they immediately scored with “It’s Your Thing,” followed by almost three dozen Top 20 R&B hits over the next couple of decades. Four of the latter 45s also reached the Top 20 of the Billboard Hot 100, while six of their albums went Top 10 on the magazine’s mainstream Top LPs & Tapes chart.

Why did the Isleys quit Motown? Clearly, they were struggling to repeat the commercial success of “This Old Heart Of Mine,” but creatively, there was change afoot, too. In the meantime, the lawyers stepped up. Motown alleged that the Isleys cut “It’s Your Thing” in November 1968, while its contracts with them were still in force. The brothers counter-claimed that the song was laid down later, in January 1969. The matter went to a jury trial, which Motown lost. The dispute continued for years until another jury returned a verdict also in the Isleys’ favour, even though they had repudiated some of their previous testimony.

BECOMING AN ADULT

Yet that case is not as well-known as two others involving artists’ exit from Motown: Mary Wells in 1964, and the Jacksons in 1976. The former’s significance derives from the singer being the first of Berry Gordy’s stars to leave, even as she was enjoying the biggest hit of her career.

Wells’ 21st birthday on May 13 that year – as “My Guy” reigned over the Billboard Hot 100 – empowered her to disaffirm her original Motown contracts, signed when she was a minor. (Stevie Wonder did much the same thing at age 21, although he re-signed; coincidentally, he was also born on May 13.) Wells was encouraged to quit by her husband, Herman Griffin, doubtless attracted by the prospect of a major advance from another record company – which materialised when 20th Century Fox offered $250,000 upfront (equivalent to $2.5 million today) and the singer accepted.

Goin’ places, from Motown to Epic

Sixteen years later, Wells talked about the Motown exit in an interview with Wayne Jancik for Goldmine magazine. “The reason for it was that at that time, the company was building,” she said. “And we had a few problems business-wise. And if I had been more on top of knowing more about the inside of the business, I probably wouldn’t have left.”

By 1980, it was evident that Wells’ post-Hitsville career was on a downward curve. She had enjoyed several R&B hits at 20th, but never again scaled the heights of the pop charts — although “Gigolo” (for Epic Records) was a Top 20 title on the Billboard dance charts in 1982. Wells retained the affection (and more) of fans, and evidently of former associates, too. In 1991, while suffering from lung cancer, she sued Motown for non-payment of royalties; the case was soon settled out-of-court. Although Berry Gordy no longer owned the company and was not party to the suit, he played a role in its settlement, and in helping the singer with her financial woes.

The departure of four of the Jackson 5 (Jermaine excepted) seemed more bitter, compounded by Motown’s claim to their professional name, and by the very public nature of the youngsters’ move to Epic Records, a subsidiary of giant CBS Records. Their father, Joe Jackson, organised a New York press conference on June 30, 1975, to announce the deal – nine months before the Motown contract expired. “We didn’t leave Motown for nothing,” Jackson said on that occasion. “We didn’t want to go through the next seven years [with] what happened in the last seven.”

Motown Industries’ vice chairman, Michael Roshkind, reacted in public, too. “To hold a press conference in itself is a breach of contract,” he said, apparently linked to the fact that the company had to approve the group’s interviews and publicity efforts. “We think there was malice involved and we are preparing to go to court.”

LAWSUITS BACK AND FORTH

So, it was back to the litigators. In Los Angeles, Motown filed suit against Joe Jackson, the group and CBS; Jackson countersued. Eventually, Berry Gordy was awarded damages, not least because the Jackson patriarch would not allow his sons to record anything for Motown even though they were still under contract after the Epic signing was announced. Still, it was a lot less than Gordy had sought.

In March 1976, when the Jacksons’ new deal came into effect, four of them – again, without Jermaine – sued their former label, seeking an accounting of royalties. The paperwork revealed that their royalty rate at Motown was six percent of 90 percent of wholesale; at Epic, it was reported to be 27 percent, and they were guaranteed $350,000 per album (worth $2 million today). “In this more collaborative environment,” wrote Jermaine later in his book, Michael: Through A Brother’s Eyes, “Michael and the brothers flourished as songwriters and producers, and they released some great pop music.”

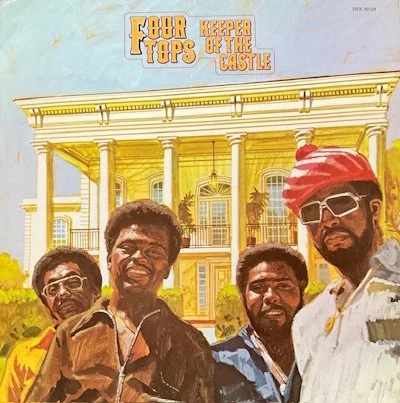

From one castle to another

Not every artist departure was publicly acrimonious. In 1972, the Spinners walked out the door of 2648 West Grand without any obvious difficulty – then again, whatever revenue they generated for Motown was considerably less than that of the Jacksons. Similarly, Brenda Holloway left amid melancholy disappointment, not rancour. “I would like to say it has been a great experience being a little part of Motown,” she wrote to Berry Gordy in 1967, even as she itemised the areas where she felt the company had let her down.

Holloway said that she did appreciate Gordy’s help in the matter of songwriting – and her co-authorship of “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy” should have bolstered her income (and that of sister Patrice) in subsequent years, as the number became something of a pop standard. She temporarily retired from the music business, but returned as a background singer, and recorded from time to time for, among others, California’s Fantasy Records.

Perhaps like Holloway, the Four Tops felt under-appreciated at Motown as the 1970s dawned, at least according to the autobiography of the group’s Duke Fakir. In I’ll Be There, he quotes Motown executive Ewart Abner as telling the quartet that they were no longer “key artists” for the company. “You guys have had a great run,” Fakir claims Abner said. “This is as far as you can go with Motown, that’s it.”

The Tops refused to let that discourage them, signing with ABC/Dunhill and returning to the Top 10 of the pop charts with “Keeper Of The Castle” and “Ain’t No Woman (Like The One I’ve Got).” When Steve Barri, one of their producers at ABC, subsequently worked for Motown, Berry Gordy casually dropped by his office, golf club in hand. Spotting Barri’s gold record award for “Ain’t No Woman,” the Motown founder joked, “Do you mind if I smash this?” The quartet re-signed with Motown in 1983, but without significant success, they moved on.

Gladys Knight & the Pips seemed to depart quietly enough, perhaps because by the time their Motown contract ended in 1973, they were sufficiently industry-experienced and had developed a connection to successful songwriter Jim Weatherly, knowing he had a copyright or two to fuel their next career move. And so it proved: his “Midnight Train To Georgia” became the quartet’s biggest post-Motown hit at Buddah Records, and the accompanying Imagination became their second Top 10 pop album.

But there was still work for lawyers. Two years after leaving Motown, Knight & the Pips sued the firm for $2.8 million for non-payment of royalties allegedly due from their recordings and songwriting. (Three years later, she sued Buddah Records, too. Then again, she was no stranger to litigation: in 1967, her manager had to take legal action against Knight for failure to pay commissions. Fifty years later, the singer sued her son Shanga to remove her name and likeness from the Gladys Knight Chicken & Waffles restaurant chain.)

THE ‘MOST COMPLEX’ DEAL

The 1970s saw other Motown exits (Martha Reeves, the Temptations, Jr. Walker, the Undisputed Truth, the Miracles minus Smokey Robinson) as did the ’80s (Diana Ross, the Commodores, Rick James, Teena Marie). Most of these did not involve litigation. If not contentious, Ross’ defection in 1981 was still newsworthy, as much because of her erstwhile romantic relationship with Berry Gordy as for the calibre of her music. She was contracted to RCA Records for North America and Britain’s EMI for the rest of the world. Why Do Fools Fall In Love was a Top 20 album on both sides of the Atlantic, and she remained prolific.

The star even returned to Motown in 1989 after its acquisition by MCA (and Boston Ventures), and she kicked things off with Workin’ Overtime, produced by Nile Rodgers. It did better chart-wise in the U.K., as did 1995’s Take Me Higher — a Top 10 title there. Ross’ most recent album, Thank You, was released in 2021 by Universal Music’s Decca label.

Smokey Robinson remained on the Motown roster for a couple of years after its 1988 sale, but then proceeded to make a variety of albums for different firms. His most recent? Last year’s What The World Needs Now for independent Gaither Music. Stevie Wonder, despite having the longest-ever contractual ties (almost 60 years) to Motown, did eventually depart in 2020, with a deal for his own label, So What The Fuss Music, via Universal Music’s Republic Records. But so far, no new album.

The final adieu worth considering here is that of Marvin Gaye. Among Motown stars, he was unique in his closeness to the Gordy family, with his 1963 marriage to Anna Gordy making him brother-in-law to the boss. So when Berry and Marvin agreed to a contractual separation in 1980, the hard work began.

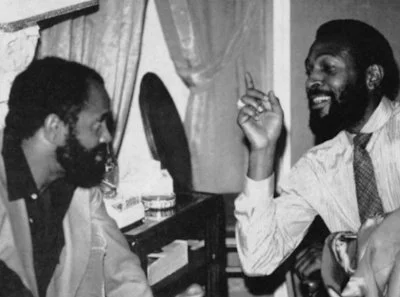

‘Berry, I’m going to leave’

Gaye had filed for bankruptcy a couple of years before, and was having to make substantial payments according to an agreed schedule. He was also trying to work out an alimony settlement with Anna. And, of course, he needed to find another record company willing to take on this extraordinary, complicated artist. In that respect, Gaye’s eventual signing to CBS Records’ Columbia label was “without question, the most complex I’ve ever been involved with,” CBS vice president Larkin Arnold told Billboard’s Paul Grein in March 1982.

The pact included a CBS payoff of $1.5 million to Motown – perhaps the first time the latter had earned such a princely sum from an artist’s exit – and a percentage of royalties from his future Columbia record sales. But the singer knew he had to deliver. “No matter what,” he told biographer David Ritz, “I couldn’t come up with another art album. After all, CBS was digging me out of a hole, paying off the IRS, Anna, the feds – the whole works.” He added, “I owed CBS something – at least a couple of grand slams.”

Similar pressure must have been felt by all the other original Motown artists who left, such was the company’s stature. The challenge was to assert their fundamental talent and outshine their previous commercial success, to convince themselves — and their disciples — that they were the reason for popularity and achievements, regardless of whichever record company they were obligated to.

With that, lawyers could be of little help.

Now, the statistics. Below is an arbitrary list of significant acts who had success at Motown, then departed. It shows their total of U.S. Top 20 hit singles – both R&B and pop – on the Billboard charts. (If an act had any pre-Motown hits, these are also noted.) The tally includes duets: for example, Marvin Gaye’s on-disc couplings with Mary Wells, Kim Weston and Tammi Terrell. The period covered here is 1959-1988, when Berry Gordy owned the record company. The stats also include hits by the Temptations when they re-signed with Motown in 1980. The Four Tops returned, too, in 1983, but scored no Top 20 R&B or pop hits on the Billboard best-sellers. The Miracles are excluded because they were essentially a different act when Smokey Robinson was replaced by Bill Griffin.

MARY WELLS

Motown: 12 R&B hits, 7 pop hits

Post-Motown: 4 R&B hits, no pop hits

BRENDA HOLLOWAY

Motown: 2 R&B hits, 1 pop hit

Post-Motown: no R&B hits, no pop hits

THE ISLEY BROTHERS

Pre-Motown: 1 R&B hit, 1 pop hit

Motown: 1 R&B hit, 1 pop hit

Post-Motown: 34 R&B hits, 4 pop hits

THE SPINNERS

Pre-Motown: 1 R&B hit, no pop hits

Motown: 4 R&B hits, 1 pop hit

Post-Motown: 19 R&B hits, 11 pop hits

THE FOUR TOPS

Motown: 20 R&B hits, 14 pop hits

Post-Motown: 11 R&B hits, 4 pop hits

GLADYS KNIGHT & THE PIPS

Pre-Motown: 4 R&B hits, 2 pop hits

Motown: 15 R&B hits, 8 pop hits

Post-Motown: 21 R&B hits, 6 pop hits

MARTHA & THE VANDELLAS

Motown: 13 R&B hits, 7 pop hits

Post-Motown (solo): no R&B hits, no pop hits

THE JACKSON 5/THE JACKSONS

Motown: 17 R&B hits, 13 pop hits

Post-Motown: 9 R&B hits, 5 pop hits

MICHAEL JACKSON

Motown: 8 R&B hits, 4 pop hits

Post-Motown: 18 R&B hits, 19 pop hits

JERMAINE JACKSON

Motown: 6 R&B hits, 3 pop hits

Post-Motown: 3 R&B hits, 3 pop hits

MARVIN GAYE

Motown: 51 R&B hits, 26 pop hits

Post-Motown: 3 R&B hits, 1 pop hit

DIANA ROSS (solo)

Motown: 21 R&B hits, 14 pop hits

Post-Motown: 9 R&B hits, 6 pop hits

Source notes: the legal shenanigans outlined above were usually reported in the music trade press at the time, although Nelson George’s Where Did Our Love Go is the place to read Brenda Holloway’s letter to Berry Gordy. Peter Benjaminson’s Mary Wells: The Tumultuous Life of Motown’s First Superstar covers her Motown exit in detail, while Gladys Knight’s Between Each Line of Pain and Glory is candid about her arrivals and departures. Benjaminson also details Flo Ballard’s legal difficulties vis a vis Motown, years after she left the Supremes, in The Lost Supreme. As you can tell, what this West Grand Blog edition doesn’t cover is the heated exit from Motown of songwriters/producers Holland/Dozier/Holland, which became one of the longest-running litigations in music industry history (it was eventually settled). That one is almost a book in itself.