A Woman's Way

THE DETAIL OF MOTOWN’S DISTAFF DECISION-MAKERS

Here’s a question: are Essence Carson, Cayla Cousins and Jess Clavero familiar with the names of Billie Jean Brown, Fay Hale and Georgia Ward?

Perhaps not. Then again, Brown, Hale and Ward wouldn’t have recognised the job titles of Carson, Cousins and Clavero: senior label relations manager, senior director of brand partnerships, and social brand specialist, respectively.

What’s the connection?

Motown Records, of course, and the significant responsibilities held by women – yesterday and today. “Mr. Gordy depends and relies on women,” vice president Fay Hale told Black Enterprise magazine in 1981. “Women in this company have been more readily accepted and recognised.”

Following in worthy footsteps…

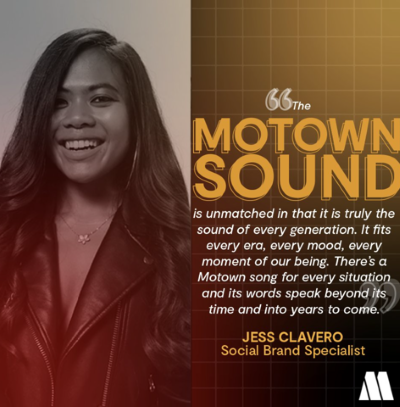

That was true from the moment it started, and 60-plus years later, it’s still true. Indeed, Motown in the 21st century had its first female president, Ethiopia Habtemariam, with the likes of Carson, Cousins and Clavero holding senior posts there. The trio, among others, were featured in the firm’s recent social media campaign to celebrate “The Motown Sound,” as pictured alongside.

So if those employees happen to be reading this, here’s more about three of the women who went before you and cleared the path, helping to build and shape what arguably became the most recognisable music “brand” in the world.

Now, this is primarily about backroom believers of the business, not creators of the music. They had unglamorous but essential jobs, handling day-to-day administration, dealing with contracts, tracking releases and storing tapes, liaising with pressing plants and distributors, invoicing and collecting. “One of the biggest moments for me,” Fay Hale told trade paper Record World around the time of Motown’s 20th anniversary, “came in billing and collection, under Mrs. Wakefield, when we got our first million-dollar collection month.”

First, a couple of caveats: this snapshot excludes Berry Gordy’s sisters – Esther, Anna, Gwen, Loucye – because of the obvious family connections. They were central to the firm’s development, but have been amply written up elsewhere; Loucye, perhaps not as much as she should (although there’s this), and Esther, likewise, given her role in preserving the Motown legacy – that is, by enabling the Motown Museum.

Still other women have been documented elsewhere, such as Raynoma Singleton, Berry Gordy’s second wife, and Maxine Powell, Motown’s mistress of etiquette. Suzanne de Passe was expected to write her autobiography for Random House, although so far, nothing. Two ladies who travelled in Motown’s business and creative lanes were Janie Bradford, spotlighted here, and Chris Clark, who ought to command her own WGB profile in future. But that’s enough exclusions – who’s up?

‘A LOT OF NERVE’

“Billie Jean Brown was feared by almost every producer in the room because they knew she ‘had my ear,’ ” wrote Berry Gordy in To Be Loved. “She had as keen a sense for what was a hit as anyone I knew.” This was the queen of Quality Control, the woman who, for most of the 1960s, ran the company’s weekly product evaluation meetings, when Motown’s department heads, senior songwriters and record producers voted on what music to release.

Billie Jean Brown, 1968

But first, to have tracks even considered for the meeting, the producers had to convince Brown, who said she had no agenda other than to bring in the best prospects for success. “See, I wasn’t personally involved in it,” she told Don Waller in 1985’s The Motown Story. “And I don’t care who you are. When you’re real close to something, you can’t be totally objective. Also, I was young and I didn’t understand some of the role-playing, the political things going on around maybe a certain track. I’d always been brought up to speak my mind. So I did.”

Brown was young, indeed: just 19 when hired part-time in 1960 to assist Loucye (Gordy) Wakefield and to write album liner notes (as mentioned here). The following year, she joined the full-time staff as a tape librarian at $22 a week, and soon impressed the boss. “She was strong, opinionated, honest, witty and had a good ear,” declared Berry Gordy. In essence, Brown was the filter between him and the producers, when he had to spend more time on Motown’s burgeoning business than on A&R. So for much of any given week, it was her job to pre-screen what was in contention for the Friday QC meeting.

“And you can’t evaluate records from a tape,” Brown explained to Waller in what may have been the only substantial interview she ever did, “which is something we took a long time trying to convince people. You cannot sit there and say, ‘This is a terrific mix,’ playing a tape. It might not go on the grooves. Some of ’em just don’t cut. They sound hot, but they will not cut without skipping. Or you’ve got to lower it so low that you lose the edge. So everything was reduced to a disc.” By 1963, Motown had installed its own disc-cutting facilities, and it was from acetates that those gathered for the product evaluation sessions heard the latest music.

For all Gordy’s confidence in Brown, she made mistakes. Probably the best-known involves Martha & the Vandellas’ “Jimmy Mack,” recorded in 1964 but unreleased for three years. Because she didn’t like it, the track was kept out of the QC meetings – and so was never put to a vote – until Gordy was pressured by Martha Reeves to review what the group had in the can. “How long,” he hollered one Friday in early 1967, “has this been on the goddamn shelf? This is a hit!” With those words, recalled by Lamont Dozier, “Jimmy Mack” was scheduled for immediate release.

On most occasions, Brown was unshakeable in her judgement, such as for “Every Little Bit Hurts” by Brenda Holloway. “Mr. Gordy didn’t want to put that out,” she recalled. “He said it was a waltz and waltzes don’t sell and the tempo was too slow and anyway, it wasn’t going to be a hit.” She eventually prevailed by calling on what he himself had said before about other unconventional recordings. “Finally, he looked over and he said to me, ‘You know, you’ve got a lot of nerve.’ ” And “Every Little Bit Hurts” was a hit.

FRIEND, HERO, MENTOR

“It didn’t strike me as being a smash of any kind, but it’s a Temptations record.” The words were those of Fay Hale, voiced in a 1964 Quality Control meeting and heard two years ago in the film documentary, Hitsville: The Making of Motown. The room had just listened to “My Girl,” and the votes were being tallied. “It’s a nice, clear sound,” added Hale, noting also that it was “different.”

Fay Janet Hale, 1980

This was another of Motown’s distaff decision-makers, who in 1976 was promoted to vice president after 15 years of dependability and versatility, handling invoices, liaising with record and tape factories, overseeing the shipment of materials to Motown’s foreign licensees and much more, including a move from Detroit to Los Angeles in 1966 to help when Shelly Berger joined the company there.

Hale came to Motown at age 30 in November 1961, having previously worked with Loucye Wakefield at the Michigan & Indiana Army Reserves in Fort Wayne, “supplying food for Nike missile sites, for the National Guard, that kind of thing,” she explained in Record World. “It helped me learn planning, organising, following through and meeting deadlines. Both jobs involved controlled situations.”

Less controllable may have been Hale’s relationship with maverick singer/songwriter/producer Andre (“Bacon Fat”) Williams, who worked with a number of Motown artists in the early years, but often crossed Berry Gordy. “She had done a lot of things for me,” Williams is quoted as saying in the liner notes of The Complete Motown Singles Volume 2: 1962, “bought me an El Dorado, put me back on my feet when things were going slow for me. Everyone at Motown thought we were going to get married. After I didn’t marry her, I drove the car back.” He also signed over a number of his copyrights to Hale, “to try to make it right.” One of those was “(If) Cleopatra Took A Chance,” co-written with Mickey Stevenson and George Gordy, and recorded by Eddie Holland in ‘62. Why the romance broke down isn’t clear, and since neither party is alive – Williams died in 2019, she passed last February – the truth may never be known. The value of her three decades at Motown is clear, however. “Missing my dear friend, my hero, my mentor,” wrote a younger colleague, Brenda Boyce, on Facebook recently, “the funny, feisty, fashionable Fay Janet Hale.”

Similarly, those who were acquainted with Georgia Ward during her 32 years with Motown are swift to pay tribute. “It seemed to me that Georgia knew more about what was going on than anyone I ever met at the company,” stated catalogue producer George Solomon. “She knew the good and the bad, but always took the high road, not repeating or participating in anything negative said about the Motown artists or executives.”

Ward had plenty of encounters and experience with them, having signed on in 1966 at age 29, first as one of the firm’s secretaries, later graduating to the A&R department. “Whoever it was – Stevie, the Temptations – would come upstairs with a cassette and play their latest stuff for us,” she reminisced for her hometown newspaper, the Buffalo News, in 1998. “We listened in its stages as it was recorded: the rhythm section, horns and strings, until at all came together. Just being upstairs from the recording studio, we could hear the downbeats from the sessions. The music would start, and your head would be going from side to side, then you’d be typing to the music.”

Ward also remembered the dress code for office staff. Women were not permitted to wear slacks, so she would journey by bus to work dressed in trousers, then change into a skirt. That said, there was open-mindedness regarding jobs and gender. “I remember when I first started, thinking, ‘Wow, there’s all these women here who aren’t secretaries.’ ”

A CALL TO MARVIN

But Ward’s secretarial skills came in handy in the spring of 1971, when the lyrics for Marvin Gaye’s new album were required for its cover art – an unusual inclusion for Motown at that point. “Marvin was in L.A. doing a movie,” Ward told Ben Edmonds for his 2001 portrait of What’s Going On, “and I was instructed to call him out there to let him know how desperately we needed them. He said he didn’t have them written out, but that he could sing them if I’d take them down.”

Marvin Gaye: a remarkable recitation

Ward’s superior saw no alternative. “So I got on the phone while he sang every single song on that album. He’d sing the words, then go back and recite them to make sure I got it right. I took down everything, some in shorthand but most in long-hand, to the last ‘doo doo doo.’ I was on the phone for hours!” One result, she added, was writer’s cramp. “I only wish that I could have sat back and enjoyed it.”

Ironically, What’s Going On again became Ward’s responsibility when she later took the job as Motown’s tape archives manager. She began dealing with George Solomon and others as they devised catalogue projects to satisfy collectors’ continuing appetite, such as 1990’s four-CD set, The Marvin Gaye Collection. Likewise, she’s credited on the 1994 compact disc reissue of What’s Going On, where the lyrics she had transcribed from Gaye appeared once more.

Between them, Ward, Hale and Brown accumulated more than 70 years in the employ of Motown Records, with a commitment and loyalty at least equal to – if not greater than – that of many of their male colleagues. Brown’s was the shortest stint, at 19 years; she left in 1979 and became an attorney, practicing in California. “When people started writing about Motown,” Barney Ales, the company’s president during her final years, once told me, “nobody ever mentioned Billie Jean, so I think she got a little crazy about that.”

At least the women who are movers and shakers at Motown Records today can be acknowledged in social media campaigns, reaching tens of thousands of civilians and, perhaps, inspiring youngsters to follow in their footsteps. But let the last word go to the man who was gender-blind when it came to staffing his business all those years ago:

“When people began talking about women with equal rights, I thought that was a step down! They ran the show: Billie Jean Brown, Fay Hale, Suzanne de Passe. My sister Esther, she was phenomenal.”

Future notes: WGB will return to the topic of Motown women soon, to shine more light on those who “ran the show.”