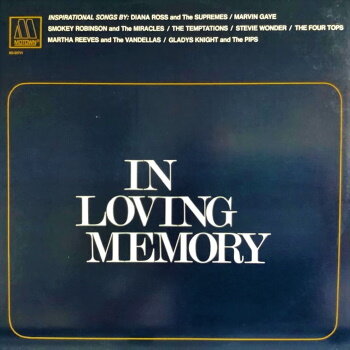

In Loving Memory

THE SISTER WHO HELPED MOTOWN TO STAY SOLVENT

The Temptations, Marvin Gaye, the Spinners and Kim Weston sang at her funeral. Brian Holland and Smokey Robinson were among the pallbearers. And tragically, the service was held on the single most important date in Motown’s existence to that point: the Supremes’ debut at the Copacabana.

Today marks exactly 55 years since Loucye Pearl Wakefield (née Gordy) died of a cerebral haemorrhage at Detroit’s Sinai Hospital. This remarkable woman was one of Motown’s earliest backroom believers, and it’s possible that had she not joined her brother at the firm, it would have gone bankrupt within a couple of years. “Loucye became the hub around which the complexities of the recording world revolved,” declared the obituary handed to mourners at the Bethel A.M.E. Church on Thursday, July 29, 1965.

Years later, Berry Gordy recalled how Wakefield gave him living space in her home before Motown existed, and how he rehearsed the Miracles in the basement there. “Loucye had been such an important person in helping us get through the years of struggle,” he declared. And her unexpected illness and death was a traumatic, tragic experience. “Berry never forgave himself,” remembered pallbearer Robinson, “always questioning his choice of doctors. In the midst of our greatest period of success, he suffered one of his greatest losses.”

Loucye Gordy Wakefield at right, with sisters Gwen (left) and Anna, and besuited Harvey Fuqua in back (photo: Motown Museum)

As most accounts of Hitsville have acknowledged, the four Gordy sisters – Esther, Anna, Gwen, Loucye – were central figures in its development and success, one way or another. But the one who died prematurely in 1965 at the age of 40 remains perhaps the least recognised.

Inside the Motown family, of course, that was not the case. “Loucye was this bubbly, vivacious girl, the fox of the family, and a beautiful lady,” recalled Marvin Gaye. “I couldn’t believe we’d ever managed without her,” said Berry Gordy’s second wife, Raynoma, of the time that Wakefield took responsibility for Motown’s distribution and accounts payable. “My biggest inspiration while recording for Motown was Louyce,” reminisced Martha Reeves. “I loved Loucye, and I would take advantage of my frequent visits to her office.” Stevie Wonder’s tutor, Ted Hull, remembered that whenever they met in the halls of Hitsville, “no matter how busy she was, Louyce always took time to chat. She was genuinely interested in what was going on in my life as much as in Stevie’s.”

Wakefield’s professional skills were in organisation, honed when she was assistant property officer of the Michigan and Indiana Army Reserves during the 1950s. Moreover, she was the first female civilian to command all vehicles, food, clothing and other supplies used for the Reserves. In this, as her funeral obituary noted, she successfully overcame dual prejudices.

Although never precisely documented, Wakefield’s switch to Motown most likely occurred in 1960 as its business dealings with pressing plants and distributors intensified. Gordy needed someone for that task while he focused on the creative side. The firm was becoming a national player, and far from Detroit, records had to be manufactured and shipped to exploit their radio airplay – that is, to sell. As importantly, Motown had to get paid by distributors, which was always a challenge for small, independent labels with few employees and modest resources, located hundreds of miles from where its hits might be happening.

MAKING CONNECTIONS, GETTING PAID

The company’s first national success was with Barrett Strong’s “Money (That’s What I Want),” but that Anna Records release was handled by Chess Records. By Gordy’s next major hit, “Shop Around” by the Miracles, he was expanding his business network with the support of Barney Ales at Detroit’s Aurora Distributing. There, Ales had handled several Tamla and Motown 45s, and helped Wakefield to identify and connect with other distributors nationwide – and, crucially, to get Motown paid.

The sacred and the spiritual, on vinyl

When Gordy presented the Miracles with a gold disc for “Shop Around” at the Michigan State Fair in early 1961, he was accompanied on stage by Wakefield and Ales. There may have been another connection: the record’s sax solo is thought to have been played by Ron Wakefield – whom Loucye had married two years earlier.

Ales joined the ranks of Motown employees in 1961 to direct promotion and sales, while Wakefield oversaw manufacturing, distribution and accounts payable. “She would handle everything from the pressing plants, shipping, billing and collections,” wrote her brother in To Be Loved, “to sales, graphics and liner notes for the album covers. A real dynamo!” Wakefield’s support team included Billie Jean Brown, Ann Dozier (Lamont’s first wife) and Fay Hale.

Barney Ales proved to be a dynamo, too, selling Motown singles and albums to its distributors as never before. But his effectiveness soon made collecting much harder for Wakefield, as Gordy explained to me several years ago. “So then I told Barney he had a promotion: I was putting him in charge of collections. He didn’t sell quite as many records because he had to make sure that [distributors] were going to pay for these, and he wouldn’t give them new records unless they paid for the old ones.” The change in duties briefly upset Wakefield, but there was compensation for her in the form of a pay raise and a promotion to vice president. She continued to oversee manufacturing and logistics, and later took over the administration of Jobete Music.

RIDING AND BOWLING

All this implies that Wakefield was a workaholic, but that was not the case. She adored horse riding – Barney Ales remembered his wife Mitzi and Loucye riding together – and instructing others in that art. She was also a fervent bowler, founding the Hitsville Bowling League and heading one of its teams.

Her death was as sudden as it was tragic. “She became suddenly ill at her desk about two weeks prior to her passing,” noted the funeral obituary. In his autobiography, Gordy vividly recounted how he dealt with the doctors treating his sister, and the guilt he felt about decisions made. “After the burial service, most of my family flew to New York for the [Supremes’] show. We dedicated the performance, and later an album, to the loving memory of Loucye Gordy Wakefield.

Loucye at right with (from left) Berry Gordy, Esther Edwards, Beans Bowles and Ardena Johnston at the Graystone Ballroom circa 1962

“It’s so strange how life can hand you some of your saddest and most triumphant moments at the same time. I thought about ‘Somewhere,’ which the Supremes would be doing in the show, and I felt my sister was somewhere close by and could hear me when I said silently, ‘Thank you, Loucye, thank you.’ ”

In the years which followed, many others had cause to be grateful. Gordy established the Loucye Wakefield Scholarship Fund to provide college education grants to high school graduates from Detroit’s ghetto neighbourhoods. Scores of youngsters were set on a different life path as a direct result. An annual fundraising ball at Berry Gordy’s luxurious mansion on West Boston Boulevard became a key part of Detroit’s high society calendar, generating tens of thousands of dollars for the scholarships. “She was the originator of ideas,” Berry Gordy, Sr. proudly told the Detroit Free Press about his late daughter during the 1971 edition of the Sterling Ball, which alone raised $50,000 (equivalent to more than $300,000 today) for the memorial fund.

And that album? In Loving Memory is one of Motown’s more unusual offerings, featuring performances of sacred and spiritual songs by a cross-section of its stars, including Marvin Gaye, the Temptations, Stevie Wonder, Smokey Robinson & the Miracles, Martha Reeves & the Vandellas, Diana Ross & the Supremes, Gladys Knight & the Pips, and the Four Tops. It was released in August 1968, with all proceeds going to the Wakefield fund, and reissued in 1981 and, on compact disc, 1995.

EXPANDING ON THE ORIGINAL

In December 2018, an expanded edition of In Loving Memory was made available in digital (not physical) form for downloading and streaming. Compiled and produced by Harry Weinger of Universal Music and Keith Hughes of Don’t Forget The Motor City, this combined the original, 12-track version of In Loving Memory (mixed from the mono master tapes) with earlier gospel recordings from Detroit circa 1965-66, overdubs, rare stereo mixes, and three additional productions by George Fowler. He had run Motown’s short-lived gospel label, Divinity, from 1962-63, cutting the Wright Specials, the Burnadettes and Liz Lands.

The 1995 reissue on CD

According to Hughes, it was three months after Wakefield’s death that producer Harvey Fuqua, with help from Johnny Bristol, recorded a dozen or so gospel sides with various acts. “In early 1966, the project moved into a higher gear,” he said. “Full orchestral versions of 14 gospel songs were recorded in Los Angeles, assigned to – and in most cases with vocals by – the Lewis Sisters. We don’t know who produced these sessions, or who wrote the arrangements,” continued Hughes. “These L.A. recordings, overdubbed by other artists, are the core of the released In Loving Memory.”

In July 1967, George Fowler was recruited to complete the project, recording a total of six sides with Ross & the Supremes, Reeves & the Vandellas, Robinson & the Miracles, and the Voices of Tabernacle. Three of these went on the 1968 album; the others were added to the 2018 edition. All told, ten of the latter’s 35 tracks were previously unissued.

Still, the best evocation of Loucye Wakefield’s personality may come not from the music dedicated to her, but from an anecdote told by her father in his memoir, Movin’ Up. The two Gordys were at a Detroit drugstore one day on Warren and Woodward. “She was usin’ the phone, and I was in the store,” he wrote. “There was a lotta other white people all over the drugstore and another man sittin’ at the counter talkin’.” One complained to the owner that “one of those niggers cut my pocket outta my coat” in an incident on Hastings Street. The proprietor replied, “ ‘Well, I’ll tell you, I hate those sonofabitches, I wish they were all dead!’ ”

Gordy senior “opened the phone-booth door where Loucye was talkin’ on the phone and I said, ‘Listen, listen, listen!’ She stopped talkin’ and leaned her head out the door. The man repeated, ‘I wish they all were dead!’ Loucye dropped the phone and rushed out the door and started to say somethin’ to that man.” Her father quickly told her to be silent, for fear of the moment turning ugly. “She was full, she was just ’bout to burst.”

Hers was a lively spirit, then, evidently not cowed by ignorance or racial prejudice. In time, Motown Records proved to be a beacon to outshine such things, and Loucye Pearl Wakefield had helped to make that a reality.

Music notes: as noted above, the expanded edition of In Loving Memory is available for digital download and streaming, so this link is one way of accessing its sacred seriousness. Personally speaking, I was always taken with Gladys Knight’s intense, powerful performances. Others must have felt the same, since she (with the Pips) was the only frontline Motown act to have two tracks, “Just A Closer Walk With Thee” and “How Great Thou Art,” on the original 1968 release. As for details of recording dates, songwriters and producers, The Second Disc listed those when it reported news of the 2018 set, linked here.

Minutiae: the contemporary press reports of Loucye Wakefield’s passing put her age at 36, which was presumably information provided by Motown. Her gravestone at Detroit’s Woodlawn Cemetery shows the year of her birth as 1924; she was born on Christmas Eve.