Hollywood, Wild and Wooly

BILLY DEE WILLIAMS REFLECTS ON HIS MOTOWN ADVENTURES

Not one, but two Motown recording artists were considered for the role of Billie Holiday in Lady Sings The Blues. Well, OK, one of them was contracted to the company after the movie came out…

Welcome to a Hollywood edition of West Grand Blog, just a few days ahead of the 80th birthday of Diana Ross, whose astonishing multimedia career includes an Oscar nomination for best actress in Lady Sings The Blues – only the second time in history that a black woman secured such recognition.

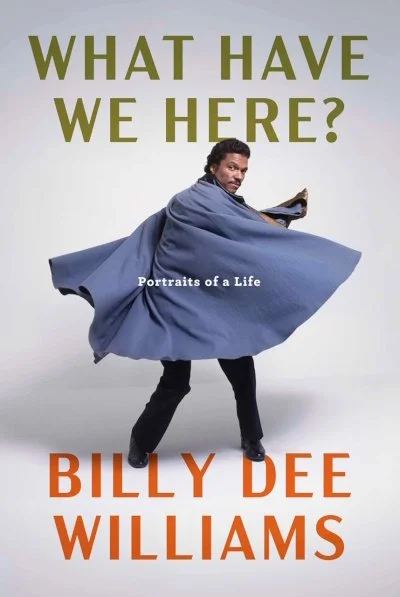

This particular topic is sparked by the recent publication of What Have We Here? Portraits of a Life, the autobiography of actor Billy Dee Williams. He was, of course, Diana’s leading man in Lady Sings The Blues and in Motown’s next major movie production, Mahogany.

Moreover, Williams was signed to Motown’s talent management division through the 1970s, and also starred in the parent company’s 1977 film about composer Scott Joplin’s life and music (and in which the Commodores played a group of minstrel singers).

A native New Yorker born in 1937, the actor came to be known as “the black Clark Gable,” and later achieved global fame as Lando Calrissian in The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi. Williams also portrayed civil rights titan Rev. Martin Luther King in Broadway’s I Have A Dream in 1976, and appeared in television’s Dynasty franchise in 1984-85, opposite Diahann Carroll.

That onetime Motown recording artist – whose album for the label, Diahann Carroll, came out in 1974, produced by Joe Porter – originally knew Williams when both attended New York’s High School of Music and Art. “There was,” he writes in What Have We Here?, “no mistaking the blinding light of stardom when Diahann Carroll walked through the hallway. She was only two years ahead of me, but she was way ahead of me and everyone else at Music and Art.”

It was up-and-coming film producer Jay Weston who considered Carroll for the lead in the movie he sought to make about Billie Holiday (he had earlier bought such rights from her). Carroll was dating Sidney Poitier when Weston was involved with the Poitier-starring movie, For Love of Ivy. “She wasn’t particularly interested in doing Billie Holiday,” he later told the Hollywood Reporter. “Abbey Lincoln would [also] have been great in it, but unfortunately her husband Max Roach, the drummer, was forbidding her to do any more movies after she did For Love of Ivy with me.”

Coincidentally, there were Motown connections even then: Billy Eckstine’s final album for the company featured the title song of For Love of Ivy as its title track; he also revived Holiday’s “God Bless The Child” therein. And Abbey Lincoln had starred in Nothing But A Man, the 1964 movie for which Motown provided the soundtrack album, its first such venture.

Jay Weston persevered with his passion, commissioning a script for Lady Sings The Blues from Canadian writer Terence McCloy and attracting director Sidney Furie. Then, impressed by seeing Diana Ross in concert and learning of her interest in Holiday, he approached Berry Gordy about making the film. It took several attempts to convince him of the idea’s virtue, but eventually, on November 19, 1970, Weston and Furie met with Gordy and Jim White, his production VP, at Motown’s Hollywood offices. After hearing Weston’s latest pitch, Gordy said, “Let’s cut a deal.” Soon enough, the project was presented to movie studios, and Paramount stepped up.

‘YOUNG BLACK UPSTARTS’

Jim White was something of a mystery man at Motown Productions, about whom I asked Chris Clark a couple of years ago. “He was a smart, kind of casual, youngish white guy…who wore suits,” she said. “And I think helped run smooth the path between Motown and Paramount.” Clark, of course, rewrote McCloy’s original script with Suzanne de Passe, for which all three were Oscar-nominated soon after the movie was released and acclaimed in October 1972.

“We were young black upstarts who burst into their editing rooms and started making changes,” Clark told me, “like we owned it or knew something about making movies. I know The Ol’ Man had to sell [Paramount] the foreign rights to get to stay in the kitchen and fuck with the footage.”

But back to Billy Dee Williams, who recalls in What Have We Here? that Gordy saw the film as a movie-star-making vehicle for Ross, “with a dashing leading man role that could add the romance he envisioned.” Williams was asked to read for the part of Louis McKay, Holiday’s third husband. “In real life,” the actor writes, “Louis McKay was an unsavory hustler and pimp, but, in Berry’s version, he was a faithful admirer, protector, lover, and ultimately a failed hero for not being able to save her.”

Williams admits he bungled his first reading for the part, mirroring what Gordy wrote about that in To Be Loved. “Nevertheless, he had a feeling about me, and I was asked back to test with Diana.” He adds, “That moment was magic. Our special connection was immediate.” The actor continues, “I could see the heat on her skin. I have no doubt Berry saw it, too. That was his genius. He had a sixth, seventh, and eighth sense when it came to talent.”

His leading man’s role and his relationship with Ross occupies a substantial part of Williams’ autobiography, including recollections of their next picture together, Mahogany. “By the time work began,” he reflects, “Diana and Berry’s real-life love affair had come to an end, but that didn’t interfere with the shared mission of making a hit movie.”

Then and since, both Mahogany and Lady Sings The Blues have been extensively written and talked about – and in the case of the latter, the 2005 DVD edition included verbal commentary by Gordy, Furie and Shelly Berger, who steered Williams’ career at Gordy’s Multimedia Management arm.

Another Motown project for which the thespian was tapped was about Scott Joplin. “I wanted to be involved. I loved ragtime. I also saw an opportunity to interpret this great American composer in a way that might surprise people.” Nonetheless, the outcome was not a major hit. “After scoring well with test audiences,” Williams remembers, “Scott Joplin was given a brief theatrical release before premiering on TV as a special event. I thought the movie deserved more recognition than it received.”

Before his career exploded with the Star Wars movies, Williams admits there was disappointment. “My manager was unable to find another big-budget romantic drama for me. You’d think that after Lady and Mahogany, the scripts would have flooded in, and that finding the next great love story wouldn’t have been a problem. But the studios weren’t making those kind of movies (or any other kind) for Black audiences. The lack of diversity in front of and behind the camera and among the executive ranks at the studios was not talked about back then, not like it would be in the coming decades, and I was among those who paid the price.”

Still, let’s close with a cheerier recollection of the Motown movie years – once more from Chris Clark – and of Gordy’s ambitions for Lady Sings The Blues. “At one point,” Clark remembered, “he made [Paramount] run all the sound past me. And they most certainly didn’t like it. They gave me so much grief with their little movieola editing machines that he finally forced them to run every single piece of footage in a screening room so he could have somebody videotape it for me, so I could take it to the hotel and work out the changes we made.

“We were wild and wooly…but our hearts were in the right place.”

Lady Day notes: as noted above, Motown’s move into movies has been well-documented, particularly the Billie Holiday biopic. Author J. Randy Taraborrelli’s Call Her Miss Ross, for one, has insights galore, while The Diana Ross Project offers perhaps the most thorough account of the film’s history. And not forgetting how the Four Tops’ Levi Stubbs was initially offered the Louis McKay part by Berry Gordy, but declined it because there was no role for his fellow Tops, as told recently in Duke Fakir’s autobiography, I’ll Be There.

Music notes: both the Lady Sings The Blues and Mahogany soundtracks can be heard on streaming services, although not Diahann Carroll’s Motown album. Much of Billie Holiday’s body of work is available there, as is Billy Eckstine’s “For Love Of Ivy” (but not his long-player of that name). Billy Dee Williams’ 1961 album for Prestige Records, Let’s Misbehave, can be found, too – and his later spoken-word appearance on his buddy Rick James’ Cold Blooded LP, on the track, “Tell Me (What You Want).” For a sample of this, here’s the latest West Grand playlist.