A ‘Life’ of Motown

VISUALLY FAMILIAR, BUT NO LESS ARRESTING

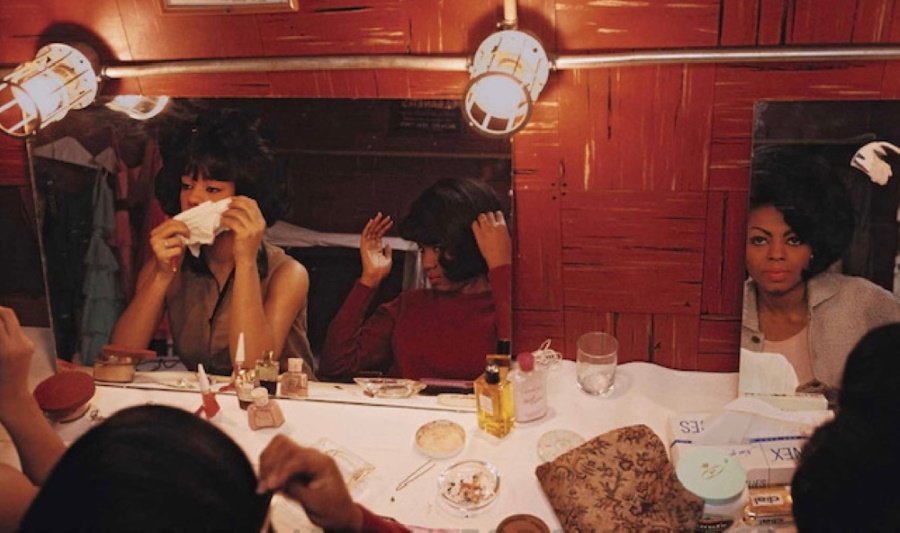

It’s one of the most captivating photographs of the Supremes’ career, gorgeous in its colour and intensity, revealing in its reflection of backstage life.

Bruce Davidson was the photographer, given access to the trio as they prepped and preened for a show in New York in 1965.

And now the image makes a return appearance, courtesy of the latest owners of America’s Life magazine, which visually documented some of the 20th century’s most significant and intriguing moments.

Life in the dressing room, New York, 1965

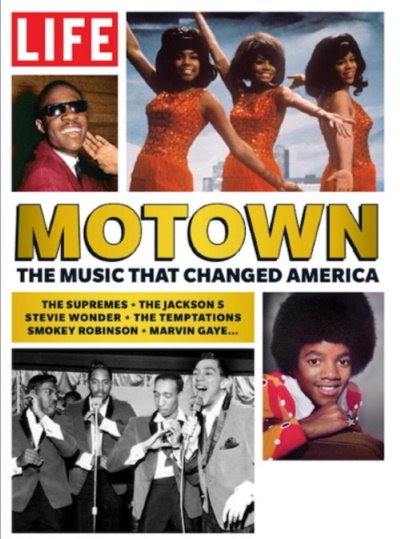

New York’s Dotdash Meredith has published a one-off Life edition, Motown: The Music That Changed America, filled with colour and black-and-white photographs of Hitsville’s music makers from the 1960s to the ‘80s. The magazine also features new essays about Motown’s place in history, sidebars about the likes of Holland/Dozier/Holland, the Funk Brothers and Maxine Powell, and a short Q&A with Smokey Robinson.

Life is no longer a weekly publication, but Dotdash has this year produced one-off special issues about Paul McCartney, Billy Joel, Queen Elizabeth II and, er, Def Leppard. The 80-page Motown edition, published on October 14, is being sold via Amazon (for $14.99 in the U.S., £10.99 in the U.K.) and printed on demand. It’s also appearing in public libraries on both sides of the Atlantic.

In addition to Bruce Davidson’s New York shot, there are his images of the Supremes on West Grand, exchanging snowballs; of the trio recording in the Snakepit, alongside Hank Cosby; and of Diana Ross, walking in Harlem, attached to Berry Gordy. Davidson was one of the era’s most highly regarded photographers, not least for powerfully documenting the era’s civil-rights struggle. “I look at my contact sheets like musical notes on a score – it’s the way I saw something, how long I saw it, whether I overlooked it or whether it was meaningful,” he told AnOther magazine in 2019.

Many of the photos in the Life one-off will be familiar to ardent Motown followers, including Lawrence Schiller’s snap of an exuberant Jackson 5 on a Malibu beach, and John Olson’s portrait of those same brothers (and their parents) at their Los Angeles home, by its swimming pool.

MARVIN IN THE CANYON

Still, some images are undimmed by time. One such is Jim Britt’s perspective of Marvin Gaye, relaxing horizontally in a Topanga Canyon house, an electric piano outside the window, overlooking the hills. Another, taken by Ken Feil, shows Gaye sitting (in a plastic chair) at the keyboard of a grand in Washington. D.C., rehearsing for his historic 1972 concert at the city’s Kennedy Center. Working with him is arranger David Van DePitte, as tapes, papers, a microphone and an aromatic candle clutter the top of the piano.

Life in 2022

Other familiar but arresting images in the magazine include one of the Four Tops under the tutelage of Cholly Atkins, as he calibrates their choreography in the basement of the Apollo Theater, and a bird’s eye view of a clutch of Motown acts in London, rehearsing for their appearance in a U.K. television special, hosted by Dusty Springfield.

Essays by Keith Murphy and Eileen Daspin recount Hitsville history from today’s perspective, thoroughly. Again, it’s well-known terrain, as are the sidebars. The work is weighed in favour of the company’s evolution and achievements, rather than its artists – that’s where the photos do the work – while the Smokey interview yields only generic, broad-brush answers.

Some of the captions are wrong. A photo of Martha Reeves said to be circa 1960 is, in fact, from 1965, when she stood in front of a record store in Liverpool, England. A shot of Marvin Gaye and senior exec Barney Ales is pegged as from 1961, when it was actually taken as the singer received gold discs for 1968’s “I Heard It Through The Grapevine.”

Perhaps more disappointing is the missed opportunity to draw from Life magazine’s own contemporary reporting of Motown’s impact and influence, such as columnist Barry Farrell’s “Farewell, more or less, to the Supremes,” in the February 13, 1970 issue, excerpted here:

“Diana has to do her thing. ‘She’s got this quality…’ says the vice president of Motown, ‘…tough to put your finger on. Maybe commercial is the word.’ Not commercial in the bad sense. Commercial only in the wish to please the kind of audience you get in the good rooms. Conventioneers, big spenders, the kind of people who want to hear People and Big Spender. Singing these songs involves a certain clash of cliches, if you come from the ghetto, especially if honesty is a very special word with you, as it is with Diana. But she sings every song as though she means it, even The Impossible Dream.”

BOB, BERRY AND BACKGAMMON

Or this excerpted assessment of Motown’s re-invention via Norman Whitfield and the Temptations’ “Cloud Nine,” by popular culture writer Albert Goldman, in the July 25, 1969 issue:

“What these strange sounds from Detroit indicate is that Motown has once again laid its cross hairs on the heart of the urban American negro. Once again it has divined the condition of its public with a perception that surpasses the best efforts of James Baldwin, Eldridge Cleaver, Rap Brown and all those who merely speak for the black man. The soul these songs have mirrored in the past was that of a man whose natural condition is anxiety. Now that anxiety has been amplified still further and counterpointed against a mysterious ancestral sound which promises salvation: the power to mount above the troubled present to a throne of pride and power beyond the white man’s ken.”

Life at home with the family, Los Angeles, 1972

Then there’s this frisson of a photograph from the December 8, 1972 edition. It ran as part of a Diana Ross cover feature (“The star shows off home, husband and babies”) and pictured her then-spouse, Bob Silberstein, competing on a shag-carpeted floor with Berry Gordy, watched by the singer, her 15-month-old daughter Rhonda and her mother Ernestine Ross, Gordy’s father (“Pops”) and Motown VP Mike Roshkind. An interesting assembly at any time, but especially considering what we now know (but didn’t know then) about father and daughter. And who won that particular game of backgammon?

As for the Jackson 5 – swimming pool aside – they could have been pictured as on the Life cover of September 24, 1971 (“Rock stars at home with their parents”) amid gold discs and framed pages of Billboard and Cash Box charts. Or recalled with these words in another Albert Goldman review from the magazine, ten months earlier:

“When Michael leads the Jackson 5 out under the arc lamps of some vast sports arena where 20,000 kids have been on tenterhooks through an hour of warm-up bands, jive-talking DJ salutes and nonstop consumption of hot dogs and ice cream, there is an explosion of adolescent chemistry that rivals the first teen bombs detonated by the Beatles. Sheets of screams hang in the air, hysterically contorted mouths and hands rise to the lights, scrimmages clog the aisles – the air of the corrida, the cockfight, the gladiatorial combat fills the plastic vastness. Then as the first song begins, the whole crowd is silenced.”

It’s always fun to read (or be reminded) how these events were reported at the time. Just as it’s encouraging to see a present-day publishing company believe that there’s still a market for 50- and 60-year-old images, and for yet another visit to the accomplishments of America’s most famous black-owned business.

“The Sound of Young America” may just be ageless, after all.

Book notes: this link offers an excerpt from the Life edition detailed above, plus some of the featured photos. And if you want even more visual history of Hitsville U.S.A., there’s always (ahem) Motown: The Sound of Young America, my book with Barney Ales. A good Christmas gift, perhaps 😉