Detroit '67

STORIES FROM THE FRONT LINE: NOWHERE TO RUN

Obviously, no one present can extinguish it from their memories.

Fiftieth anniversaries are seductive creatures, assured of attention, polished and ready for their close-up, aglow with historical context. This Sunday, July 23, will mark a half-century since the calamitous riots of ’67 ravaged Detroit; American media coverage has been building for weeks. You can expect even more, not least because of Kathryn Bigelow’s imminent new film, Detroit, which is set in that dramatic time and place.

For those interested in the Motown perspective, there are memories, music, anecdotes and ironies. One of these is the fact that the Detroit soundtrack album will be released by “modern” Motown Records, featuring music from the company’s past. It includes Martha & the Vandellas’ “Jimmy Mack” (recorded in a more innocent 1964), Brenda Holloway’s “Till Johnny Comes” and the Elgins' "Heaven Must Have Sent You."

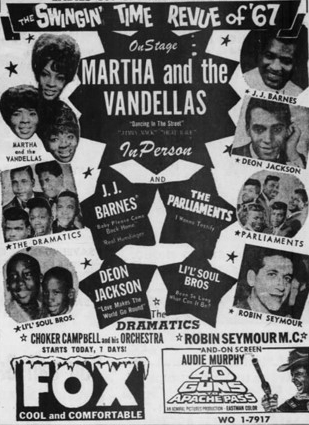

Martha was recently interviewed by Jeff Karoub of Associated Press in Detroit. She offered her first-hand, familiar anecdote about being at the Fox Theatre on July 23, 1967 – some ten hours after the original “blind pig” incident at 12th and Clairmount which sparked the riots – and spoke about how unnerving it was to tell a largely young audience what was happening in their city. “Imagine going out there lighthearted and ready to work,” Martha said. “My heart was beating so fast after returning to the dressing room.” Read the full AP story here.

Fox Theatre ad in the Detroit Free Press

The Fox show’s MC, Robin Seymour, also remembered the drama when I spoke to him while researching Motown: The Sound of Young America. There were six acts on the bill, including J.J. Barnes, the Dramatics and the Parliaments, with Martha and her group headlining; four performances were scheduled for that Sunday. “The police came in, I guess it was about noon or one o’clock,” said Robin, “and we were ready to start the second show. The theatre wasn’t even half-full. They told us what was going on, that we would have to stop the show, and make an announcement for the kids to quietly leave.

“Martha got out on the stage and very carefully said, ‘Boys and girls and kids, there’s some trouble out there. We’re not going to be able to continue with our programme. Those of you who are waiting for your moms and dads, just wait in the lobby. Those of you who have transportation, fine, but be careful out there if you’re driving.’ And [the police] made an announcement about what streets to avoid.”

The next day, Robin’s popular, live Swingin’ Time programme on Windsor’s CKLW-TV went off the air, replaced by reruns. He told me, “I wish I had recorded what we said when we came back: ‘We’re just a bunch of kids, we’re all just one, and it’s time for us all to live and grow together.’ We came back on-air on Wednesday [July 26], and it was just kids from Windsor who were there.” It took another week, the DJ said, before Detroit youngsters made the river crossing once more to join the show’s audience, dancing in the studio.

What Seymour glimpsed outside the Fox that Sunday was unforgettable. “You could see the pillars of smoke in the air from different sections [of the city]. It reminded me of when I was in Germany during the war. Made me sick to my stomach. That was the moment Detroit changed.”

Motown’s onetime A&R director, Mickey Stevenson, had left the record company by the time of the riots, but not Detroit. “I was maybe two blocks from where it started,” he explained, “and you couldn’t do anything. You could look out the window and see all the stuff going on. I could see the stealing and robbing and acting crazy. It was crazy, frightening, like a warzone.”

Military might in Detroit (photo: Vernon Brown)

That summer, future Motown vice president Miller London was working at the motor city’s Stark Hickey Ford dealership (he joined Hitsville two years later). “That riot started and was provoked because of police brutality,” he emphasised. “It wasn’t so much whites against blacks, as it was back in the ’40s when they had the last riots. This was more rioting against police brutality, the way the city allowed that to happen – and people were fed up. It wasn’t a race riot, it was a riot against the establishment, as anybody who lives here [and] went through that knows.”

At the time, Miller lived near the Riviera (“Detroit’s finest all-night theatre”) on Grand River, which was temporarily taken over as a command post for state troopers tackling the turbulence. “So when I went home, the lot where people parked their cars to go to the theatre was full of tanks. And National Guard vehicles.” As the riots began in the early hours of July 23, the Riviera was screening Born Losers.

As for the Motown headquarters on West Grand, what happened there that week has been depicted in various ways. There’s a scene in Motown The Musical in which Berry Gordy's character is touched by the solidarity of his staff and their determination – whether white or black – to stick together. The Motown founder told me that he had instructed his white employees to leave. “ ‘Look, this is a race riot,’ ” he advised vice president Barney Ales. “ ‘You people should get out of here and go home.’ And they were saying, ‘No, this is our home,’ and they stood there with the fires getting closer. I was trying to protect them, and they were trying to protect me, and Hitsville.”

Certainly, Gordy, Ales and promotion manager Gordon Prince were present. “I don’t know who else was at work,” Prince recalled. “We had seven or eight buildings, but we were there. I’m sure [attorney] Ralph Seltzer was there, even though I didn’t see him. He told me to be there, and if he hadn’t been, I would have hit him!” Gordon’s task was to reassure Motown’s distributors around the country, and to ensure pressing plants were still shipping the hits. The company’s best-selling 45 that July was Stevie Wonder’s “I Was Made To Love Her.” During the week of the conflagration in Detroit, it reached No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100. The single at the summit? “Light My Fire” by the Doors.

As for Studio A at Hitsville, it appears that on the day (or night) before the riot’s Sunday flash-point, Harvey Fuqua and/or Johnny Bristol were working on material for Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell, while Brian Holland and Lamont Dozier were supervising vocal overdubs on tracks for Chris Clark. Thereafter, the Motown session logs reveal no entries until August 1, by which time the uprising was quelled. Clark had flown in from Los Angeles while Detroit was burning. “I looked down from the plane and there were fires everywhere,” she remembered. Soon, though, she was in the studio, at the microphone once more.

Another out-of-town white act signed to Motown was in the city, too. “We were [staying] in a hotel in downtown Detroit,” recalled Greg Jeresek of Midwestern rock band the Messengers, who were recording at Hitsville. “I remember spending most of the day and night, kind of on the floor away from the windows, because you’d have bullets coming through sometimes, and tanks in the street. It was very exciting in one respect, and very life-threatening in another.” In the weeks which followed, Jeresek said he could feel the racial tension. The Messengers performed during Motown’s first national sales convention, staged in Detroit in late August. “A lot of people were taking sides…so there was a lot of divisiveness, and hopefully we helped a little by at least showing a black and white presence on the same stage. Who knows?”

The Messengers at Motown's sales convention, as pictured in Billboard

Arranger Wade Marcus lived half a block from where the riots began. “We had to sleep on the floor for about a week,” he said, “because the National Guard came through there, and they were shooting at everything. At night, you had to turn out all the lights. Somebody lit a cigarette in his house on the second floor somewhere, and the National Guard killed him, shot right through the window.” Detroit, said Marcus, “made those other riots look like Sunday school picnics. They had a lot of scandal with the state police, they killed a lot of people.”

Wade is someone who believes that, by 1967, Berry Gordy had sufficient political clout to ask city authorities to protect Motown’s headquarters, which were worryingly close to the riots’ epicentre. (Others dispute whether he did.) “All he had to do was call the governor,” said Marcus. “In fact, the governor at the time was a good man, George Romney, and he loved jazz. In my spare time, I used to play with a big band in Detroit, and he used to come hear us all the time.” Marcus noted that National Guardsmen did come to West Grand, “and some would plant themselves on the lawn by Motown. We never had any problem, nobody firebombing the place or wrecking the equipment.” Even so, some shots were fired at Hitsville property, damaging the sales office and smashing stone flower pots on one of the roofs.

The carnage of July 1967 underpins the story told in Detroit, which focuses on the notorious Algiers Motel killings and whose stars include John Boyega (Star Wars: The Force Awakens), Anthony Mackie and Algee Smith. With Kathryn Bigelow and cast members in attendance, the film will have its world premiere on July 25 – at the Fox Theatre.

It’s not clear whether Martha Reeves or other onetime Motown stars and starmakers will be among the invitees. Anyone who was present in Detroit fifty years earlier will never forget that summer. Whether they want to relive it at the Fox is a different matter.